Speed was the defining element of life for 17-year-old Leoni Zopp. Her entire world revolved around going as fast as possible through a blurred forest of gates to a finish line. Wrapped in a speed suit and on long, stiff skis, Zopp was one of Switzerland’s most promising alpine ski racers. For years, she trained almost daily in pursuit of her goal to become a World Cup and Olympic skier, and in 2017, it was finally starting to pay off. In a country where alpine ski racing has an almost religious heritage, Zopp was a standout prospect with a promising future.

That winter, she took home one gold and three bronze medals at the Swiss National Championships, leaving most competitors in awe. Everyone knew the young skier from Andermatt was talented, but now, her coaches and peers wondered whether Zopp might be the next big thing.

Early the following season, Zopp was in Arosa for a giant slalom competition. The weekend went as planned — she liked the course and developed a fast flow during practice. On Saturday, her first run began well, but twenty gates in, setting up for a big turn, Zopp’s right ski skidded out, and she lost balance. She crashed at over 65 km/h (40 miles per hour), tumbling and spinning 180 degrees before landing on her head and back. Medical personnel rushed to her side as those lining the course held their breath. Shaken but able to get to her feet, she managed to make her way off the course; however, it quickly became evident that she’d suffered a severe concussion.

“I had crashed many times but never had a concussion. So, even if I understood that I had to rest, I was still optimistic and thought I could continue to race soon after,” says Zopp, who was looking forward to the European Youth Olympic Games later in the season.

But after a month’s respite, primarily spent in a dark room with no screen time, things hadn’t improved. At this point, Zopp was referred to the Swiss Concussion Centre in Zürich, where she underwent tests. “They tested my eyes, concentration abilities and balance, but the scariest was when they put needles in my brain and toes to check the nervous system,” Zopp recalls.

Over the next six months, as Zopp met with a physiotherapist at the Concussion Centre several times weekly, things slowly improved. Still, there was no more skiing that winter.

The following years would be both challenging and the antithesis of her previous life as a ski racer. Gone was the relentless pursuit of speed. Instead, Zopp’s world was now slow, quiet and often dark. The concussion left her with constant headaches, memory loss, mood swings and difficulty remembering things.

In typical fashion, Zopp worked determinedly to overcome these deficits. Several times during the next two years, she tried to come back but faced setbacks after setbacks. Eventually, Zopp realized she’d have to abandon the dream of becoming a World Cup ski racer.

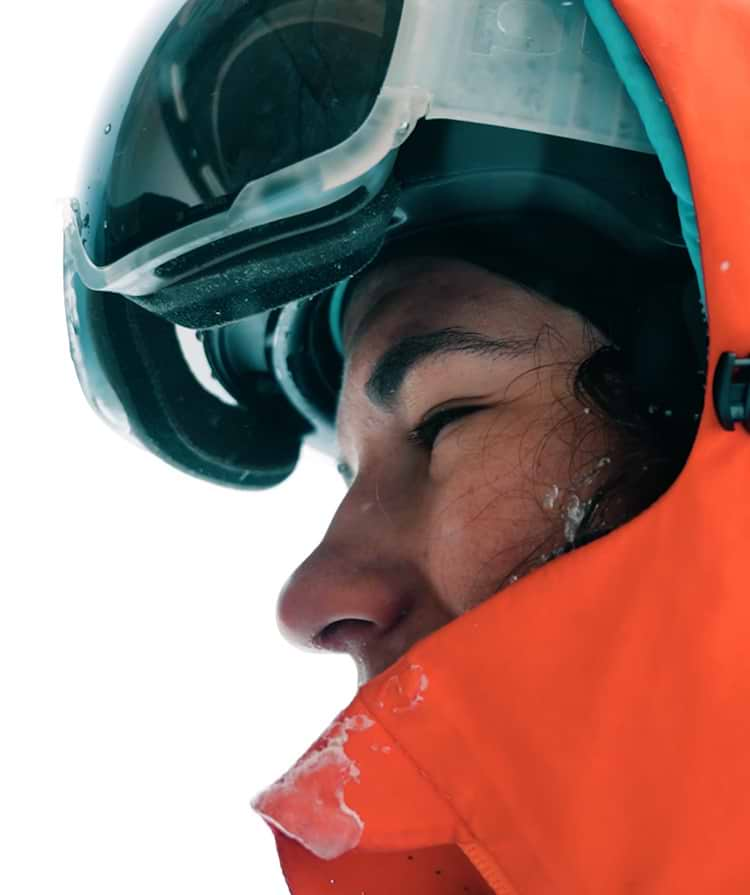

Leoni Zopp

Once Zopp put her ski-racing dream aside to heal slowly, she faced the challenge of redefining herself. Though skiing at max speed was out of the question, she couldn’t entirely turn her back on the slopes. Instead, she used the same determination that had always defined her to develop new skills as a freeskier, focusing on big mountains and the pursuit of powder. The challenge was the same — to fluidly and robustly master a snowbound environment — and, it turned out, as fulfilling as chasing speed had been.

The need to completely reinvent herself showed Zopp the power of the mind and piqued a new interest in psychology. “During recovery, my physiotherapist became such an important part of my life because he knew exactly how I felt and could guide me through my feelings. It saved me, and I became interested in learning more about mental health,” she says.

For the past three years, Zopp studied at the University of Bern, balancing her studies with more-or-less full-time skiing during winters en route to a bachelor’s degree in psychology. “Mental health is so important,” she sums. “Not everyone is as lucky as I was with so much support from family, coaches and special care. If I can give back in any way, that’s something I want to contribute to society. Hopefully, one day, I can be a therapist and help others with similar problems.”

Growing up in a small mountain town kickstarted Zopp’s life on snow, and becoming a skier was the most natural thing. Now 23 years old with a racing career behind her, Zopp calls herself an aspiring big-mountain skier. “I always loved my home mountains around Andermatt, but now I have much more time to explore them,” says Zopp, who finds going deeper into the backcountry the most fantastic way to discover the opportunities close to home — turning peaks she once admired from afar into peaks she now climbs and skis.