Back in the late 1990s, Niklas Allestig, producer of the infamous Free Radicals film series, sent me a T-shirt inscribed with a single word: “Everyturnisasignoffear.” Of course, this was a whimsical sentence disguised as a word.

But regardless of its definition, it still made perfect sense: the ski turn was invented because straight-running—as early practitioners called their crouched, linear descents—lacked control and could, depending on conditions, quickly become intimidating. The thrill of speed, which humans enjoy, was also a deterrent in this case.

The earliest attempts to solve this longstanding problem go back 4,000 years and involve a long stick that a skier, standing on heavy, long skis, could use to push into the snow to slow down. Later—and braver—some skiers placed the stick between their legs and sat on it like a witch’s broom, using their body weight to push down for braking. It didn’t always work well, as a 1920s skiing book explains: “Stick-riding, like cocaine, is useful in an emergency but devastating as a staple diet.”

Point taken. And so, the search continued for a better way to control skis. A solution was eventually found: stopping. Instead of relying on flat terrain to slow down (or a knee-wrenching snowplow in deep snow), someone discovered a way to stop by quickly unweighting and turning the skis sideways 180˚—much like a hockey stop on ice.

Ah ha. From there, it became an easy trick. What if, instead of coming to a full stop, you briefly turned your skis sideways — not completely perpendicular to the slope, but enough to stay in control — and kept moving? The ski turn was born.

In science, the practice of “reductionism” aims to analyze and describe complex phenomena by examining their simplest parts. In other words—breaking it all down. When you simplify the complex activity of skiing, the first step you encounter is the turn.

A simple example of how centrifugal and centripetal forces interact is that turns make skiing effective. It was probably rare in the sport’s early years for anyone to look back up an untracked slope after a descent and say, “Lovely straight line!” But for over a century now, it has been customary to compliment someone on their “beautiful turns.” And, as skiing is a constantly evolving activity, there are many different types of turns to comment on: snowplow, telemark, parallel, stem Christie, carved, skidded, drift, pivot, short, and jump turns all have their specific uses.

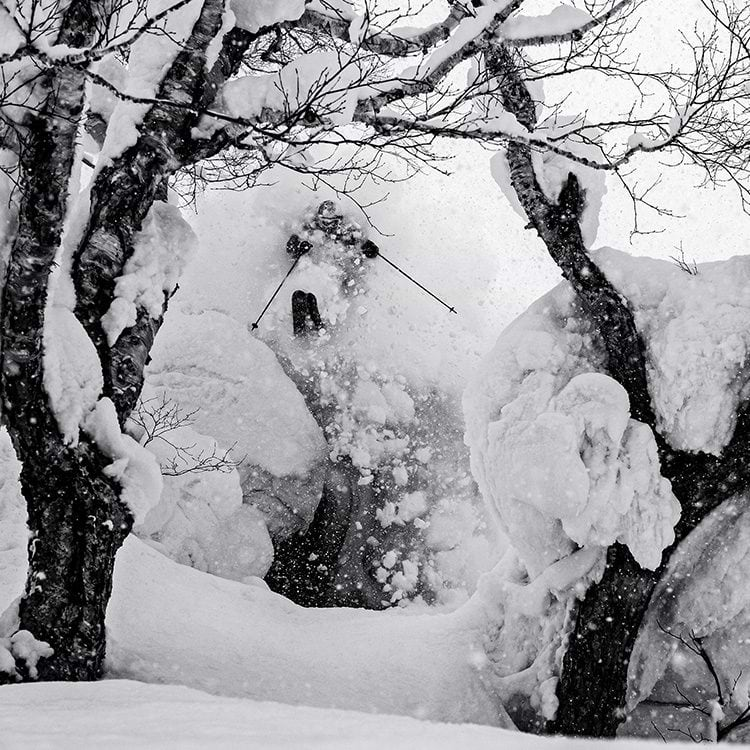

Regardless of the type, transitions between turns from one side to the other occur as the skier unweights, reducing friction with the snow to nearly nothing. There’s a well-known, sought-after deliciousness to this weightless moment. Perhaps it’s the subtle or fleeting nature of the feeling—lasting only a split second—that makes it difficult to find in any other activity. Consider this: when you speed down a deep snow slope, you naturally begin to turn, allowing yourself to lose contact with the ground momentarily without conscious effort. This is why skiing is often described as the closest experience to flying without leaving the Earth. This earthbound flight is driven by turns. Turns are how you find the perfect balance between gravity, speed, and snow conditions. Indeed, it’s fair to say that in skiing, turns are everything. After all, when friends invite each other to go skiing, how often do they say, “Let’s go make some turns!”

Ski racers, for whom a turn is more of a technical challenge than a visceral experience, are committed practitioners of reductionist thinking. By analyzing every detail of a turn—its initiation and exit, its lowest and highest points, as well as the positioning of each body part and piece of equipment at every moment—they find ways to increase speed. They also discover methods to create different types of competitions—slalom, giant slalom, downhill, and skiercross—all of which depend on mastering various aspects of turning.

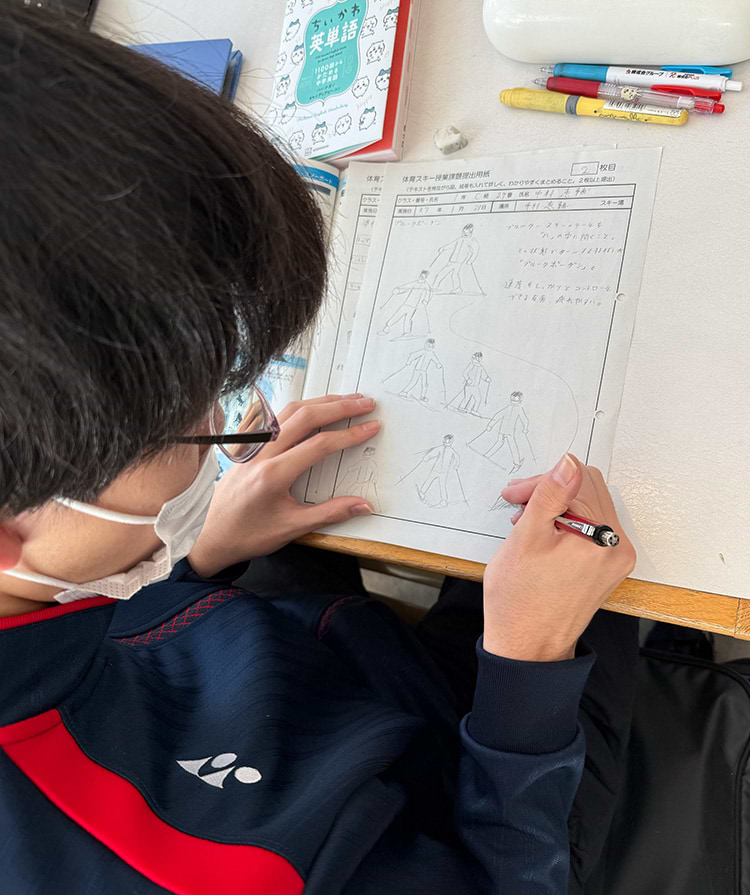

What racers know about turns has been clear from the start: they are something to study and analyze. Hundreds of books have focused on the ski turn. In Japan, as is typical of the master-apprentice tradition, students in ski academies learning about turns also need to draw them in sequence to understand the phases, body, and ski positions involved. Even then, ski knowledge doesn’t end with understanding the turn—there’s also the environment to consider.

“In many sports, properties of the playing field are relatively fixed and remain the same during play,” write David Lind and Scott Sanders in The Physics of Skiing. “That is definitely not the case in skiing… [which] can only be done on a playing field whose basic physical properties change.”

That’s because in skiing, small temperature changes cause major shifts to the surface, which, after all, is water. Since water exists in three states—solid (ice and snow), liquid (water), and gas (vapour)—the surface variation involves different amounts of each. It turns out that skiing works best near 0˚C, the so-called “triple point” of water, where all three states of water coexist. That’s why spring turns are so enjoyable: if it’s colder than 0˚C, it can be too icy and tricky; if it’s warmer, it becomes too wet and slushy. (And here you can imagine the invention of ski wax, which was likely adopted not just to reduce friction and go faster at various temperatures, but also to make turning more enjoyable.)

Ultimately, for most of us, turns are more about the feelings—whether we’re making them ourselves or spectating someone else’s. I recall watching a team at a backcountry Powder-8 contest create synchronized, symmetrical tracks, and I could literally feel each turn in my stomach every time they crossed tracks. That sensation was truly incredible. For me, every turn is a sign-off, not an invitation to accelerate, but to appreciate the art of the turn and celebrate each one.