An Analog Approach to Global Ski Culture

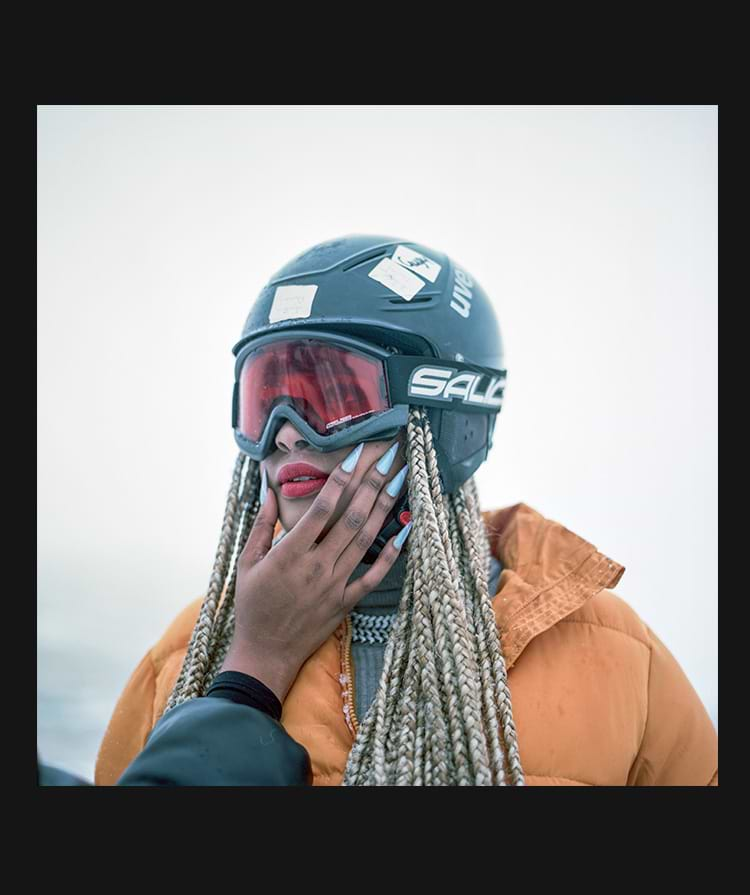

The process takes about two minutes, from when Kari Medig pulls out his 1977 Hasselblad 500C to when the shutter clicks. He deftly navigates the manual focus of the medium format camera using a waist-level viewfinder, allowing him to maintain good eye contact with his subject. Medig is patient. He always asks his subject for a neutral expression — not a smile — and waits for the moment they let down their guard. Something about the analog camera and the 50-year-old, lightly-greying father of a three-year-old feels complementary — the camera is an extension of Medig, not a shield between him and his subject.

His decision to often eschew digital cameras with large megapixel sensors and higher frame rates may partially explain the powerful intimacy that resonates when you view Medig’s work. His images make you stop to look more closely. You feel curious and slightly uncomfortable thinking, “This is different.” However, the arresting quality of his photographs is due to more than his choice of equipment.

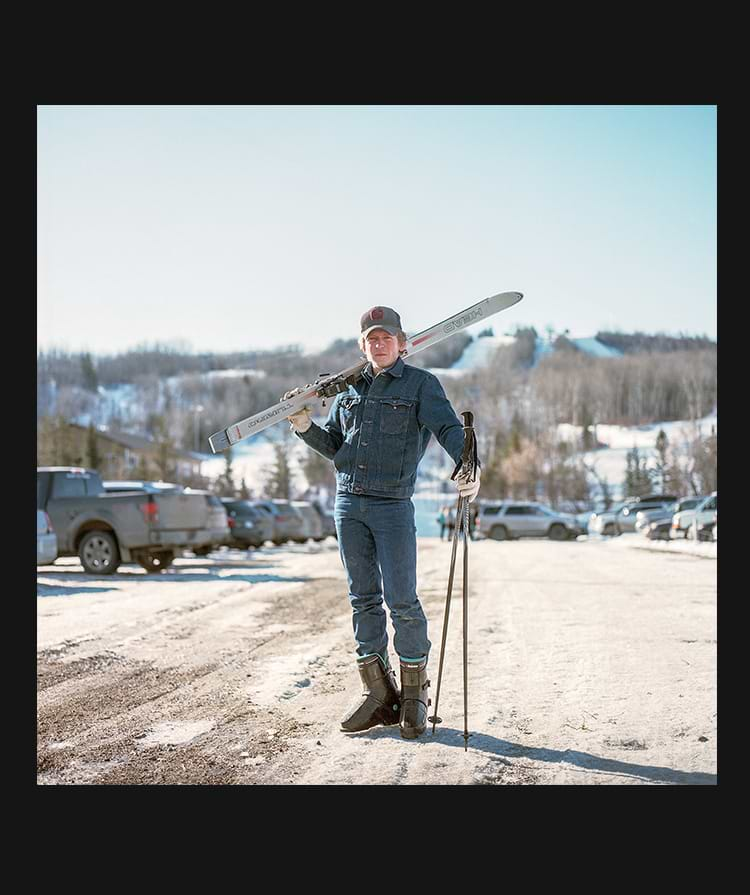

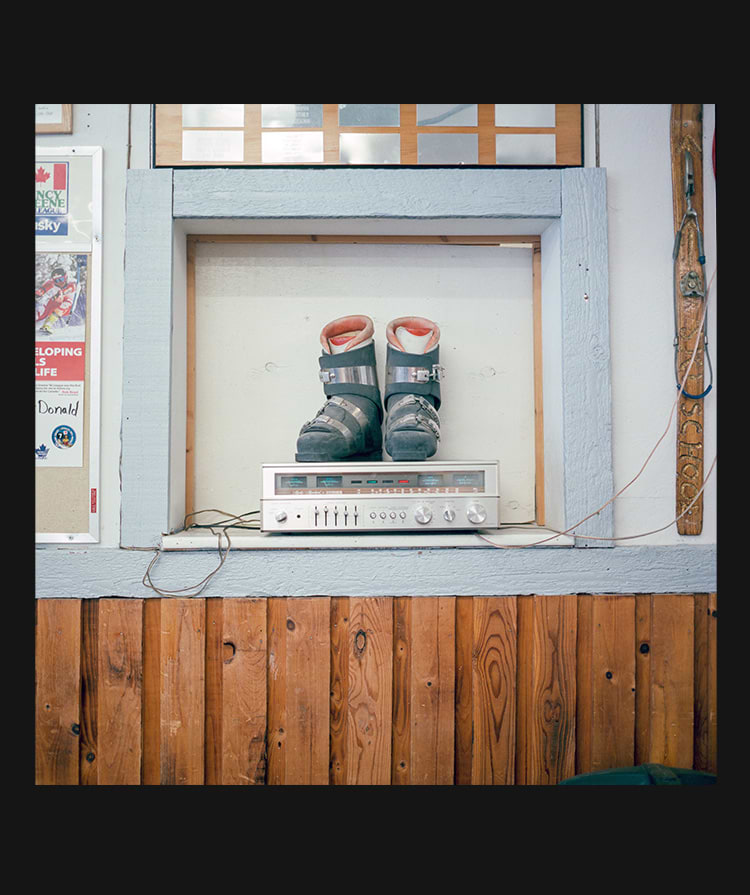

Medig’s unique vision and intentional approach became immediately evident when I met him at Whitewater Ski Area in his hometown of Nelson, BC — a stalwart of funky Kootenays ski culture, home to a bone-rattling washboard dirt road, a small yet world-renown cafeteria, and no lodging. Though the slopes of Whitewater are blessed with famous Kootenay cold smoke for much of the winter, Medig’s favourite canvas is the slushy parking lot below, with its assortment of old campers, new trucks, tired children, energetic dogs, Kootenay locals and eclectic visitors.

Fresh out of photography school, Medig apprenticed under Rick Collins, a multi-year winner of the Canadian News Photographer of the Year award, at a small newspaper in Chilliwack, BC. He was told to “shoot pictures, not film,” and learned the importance of visual storytelling.

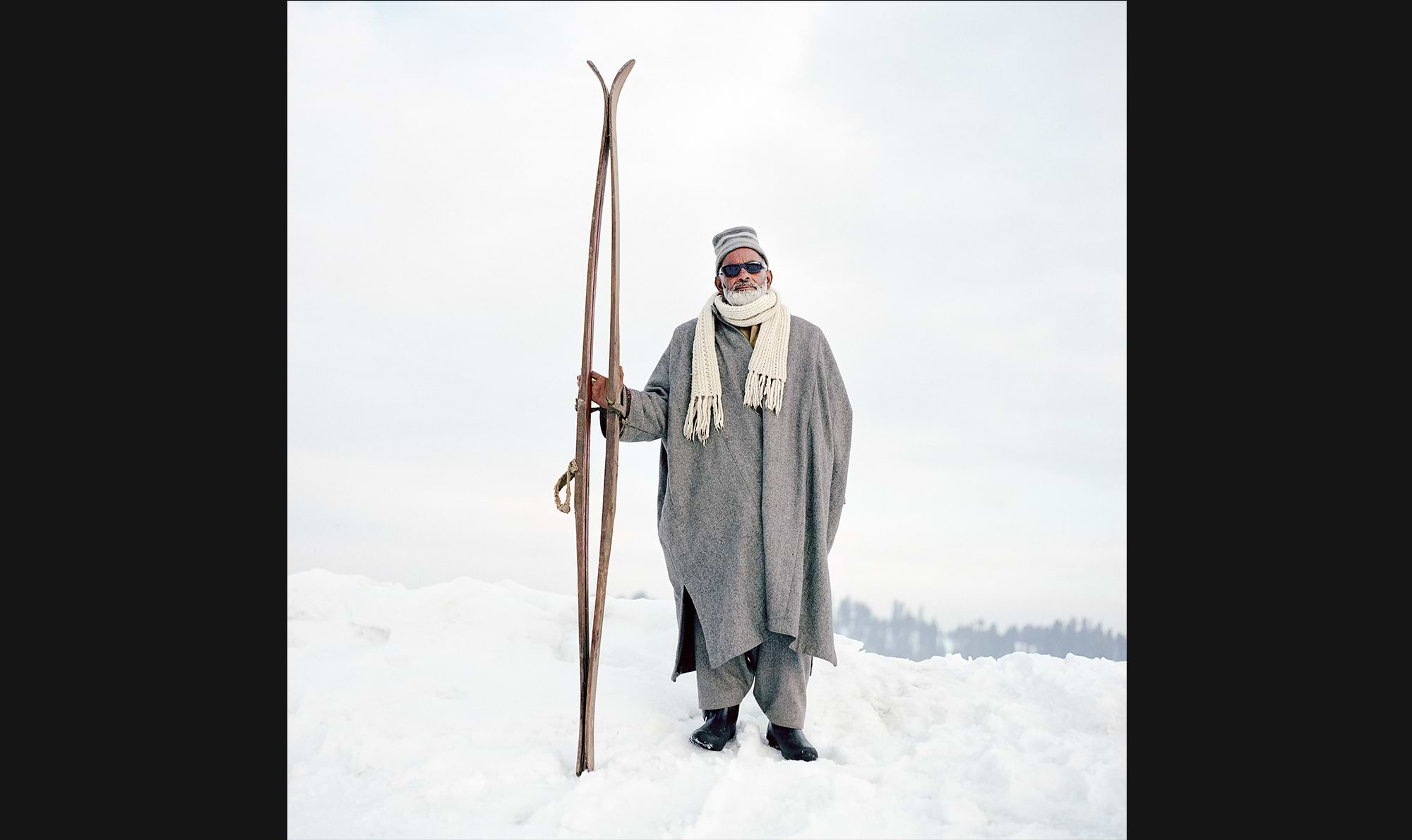

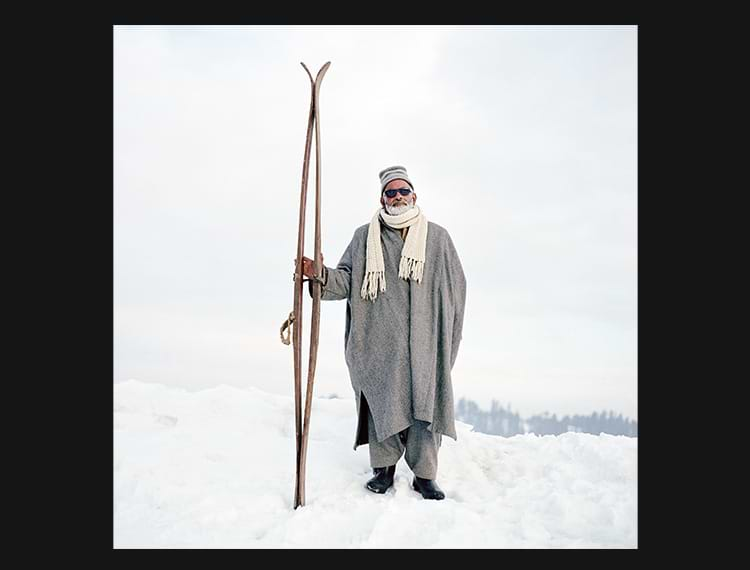

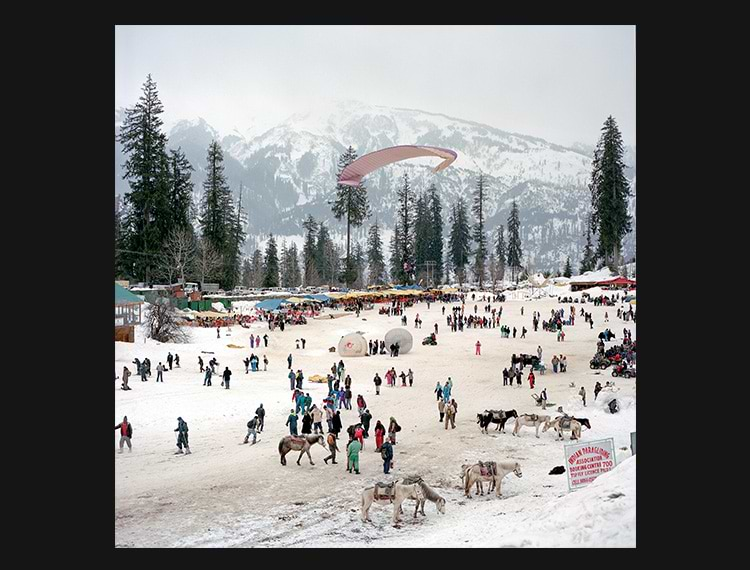

Years later, this foundation proved critical during his first ski assignment for SBC Skier Magazine in Kashmir, on the crenellated northern fringe of India. Medig and a crew of athletes were shooting at a new ski area in Gulmarg when the lift broke down.

Kari Medig

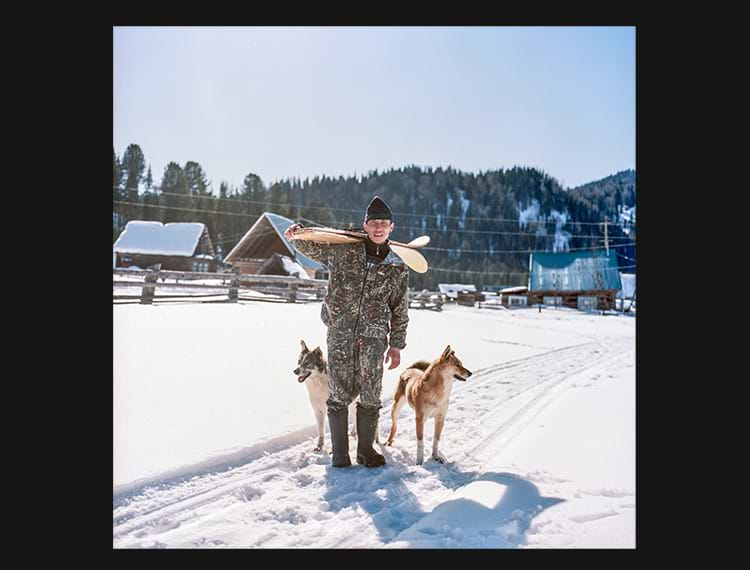

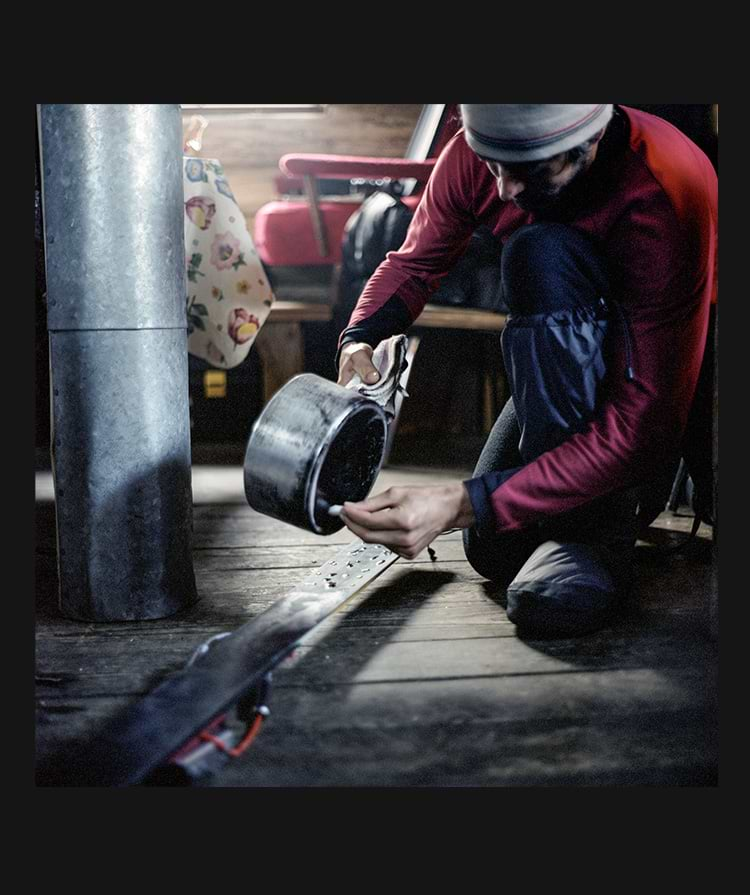

Since then, the standard action shot of classic lines and deep powder has virtually disappeared from his portfolio. Despite shooting with world-class athletes, many of Medig’s most iconic ski images have come from base areas and feature locals. More often than not, he captures these images with his trusty manual-focus Hasselblad, which is also close to 50 years old.

Kari Medig

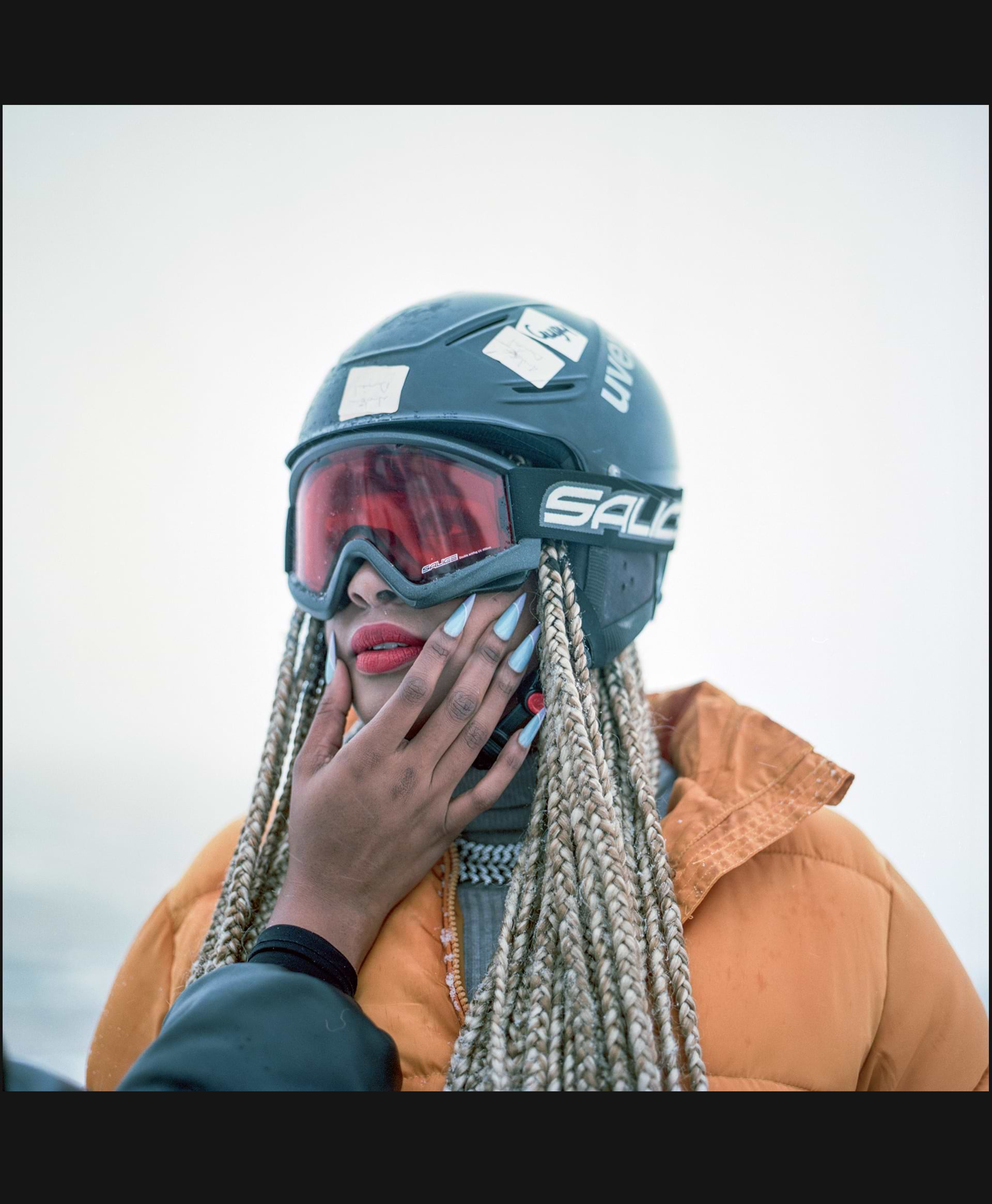

Over the past few decades, Medig has documented cultural portraits of the global ski community from Central Asia to the Baltics to Korea in a poignant series, One Thousand Words for Snow. Portraiture, Medig explains, is one of the most challenging practices in photography, reliant on infinitesimal moments of vulnerability. “That moment where the [subject] relinquishes a slight bit of control — it’s what makes it special from one frame to the next.”

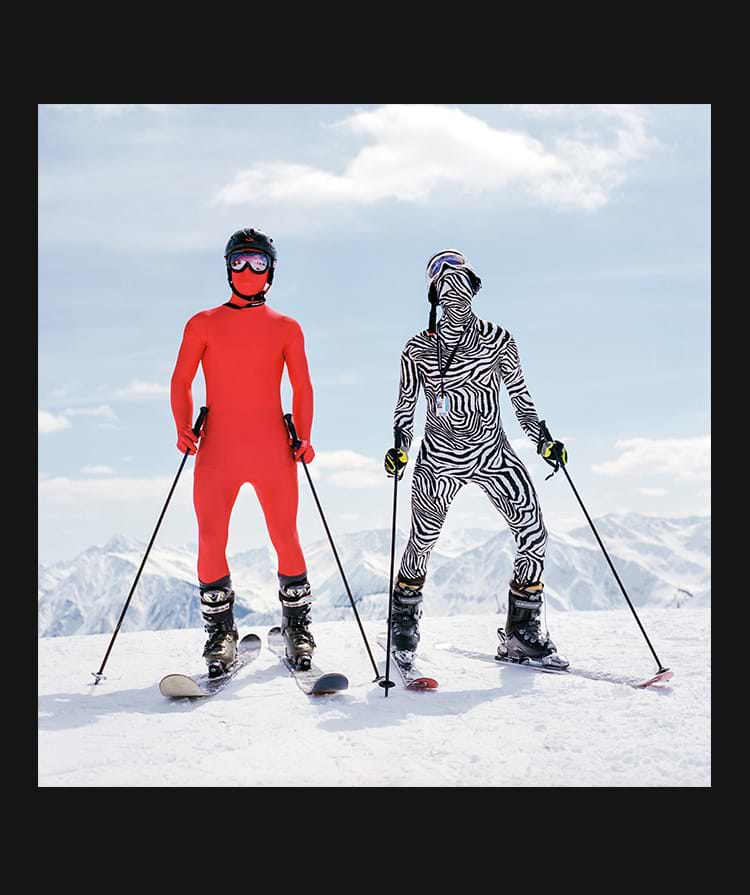

This unexpected window into the broader, more authentic world of ski culture has resonated with leading industry publications, including Powder, Forecast and SKI, which always seek to capture reader interest with something different. His tendency to turn his back on what is commonly seen as the accepted subject produces such unexpected images that Medig is also in high demand among publications significantly removed from the world of snowsports, including the Financial Times, National Geographic, and GQ.

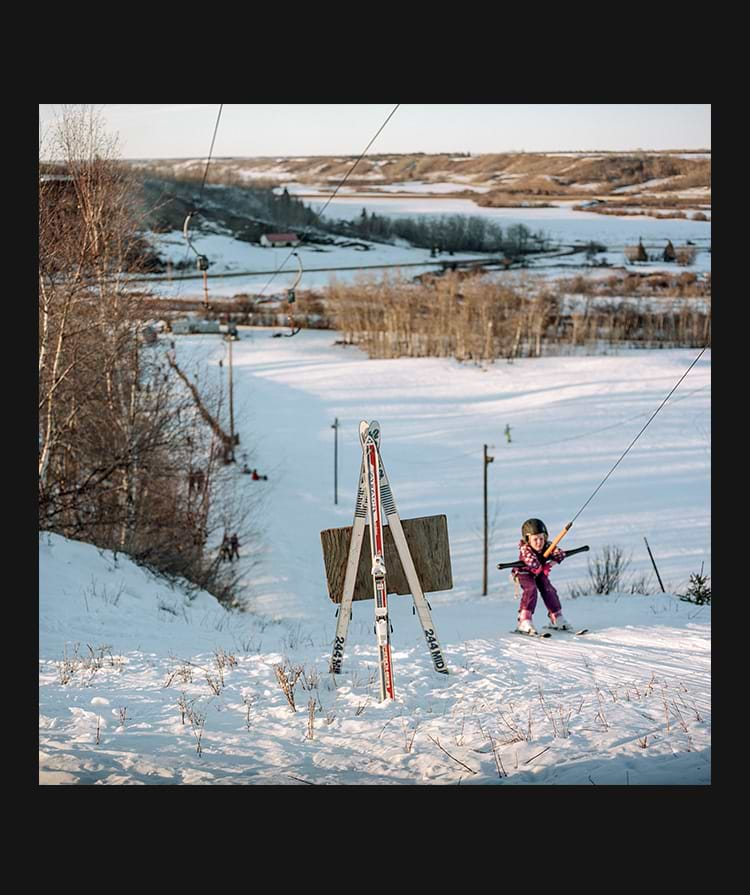

A dedicated skier himself, Medig still feels the allure of skiing’s distant corners of the earth. Yet, some of his favourite works have come from the rural, understated community hills close to home in Canada’s Prairies. It’s part of his commitment to show every facet of the ski community.

Kari Medig

This is perfectly illustrated in his cover shot for Forecast Ski Magazine Photo Annual from a few years ago, which is starkly different from the usual fare. In a placement typically reserved for the most bottomless face shots and alpenglow-bathed sunset, Medig’s image of a lone wooden sign beside a gravel road against an endlessly flat horizon may be the antithesis of what we expect in a cover shot. Black hand-painted lettering on the white sign depicts an arrow and two words: Ski Hill.

“There’s a tension between what you intellectually think a ski hill should be and what it is in some places,” says Medig. He calls the cognitive disconnect in this image a “sense of startle” — an intangible quality or secret sauce — that catapults the photo beyond the audience’s preconceptions. “There are a lot of tropes in the ski world, a lot of things we’ve come to expect, and it’s neat to play with ideas on the edge of it,” Medig continues. “It’s an area where many more of us exist than the guy hucking off the cliff.”

By that measure, Medig’s images from the seemingly far-flung fringe of skiing are not outliers insofar as they are mirrors of ourselves. More of us exist in that sphere of odd juxtapositions than in the familiar refrain most ski photographers seek. Despite the inclination to note something out of place in Medig’s photos, his images resonate when skiers recognize themselves and realize they’re not cast from a homogenized mould.

One of his recently published images came with an innocuous caption: “Still continuing to capture the edge of the ski world.” An Austrian skier saw the image and expressed a different take. “That looks like the centre of the ski world to me because it’s a little hill somewhere,” she told Medig.

Medig smiles. “She was right in a way. It’s funny how every day in skiing has become the fringe in terms of imagery and how skiing portrays itself.”

Despite the herd mentality of many action photographers, or perhaps because of it, Medig is very content to let others chase milliseconds of flying powder. At the same time, he uses his unique vision and instincts to capture the genuinely timeless moments of snowsports – the overlooked moments of ski culture — often hidden in plain sight and that most of us fail to see until captured by one of his images.